TelegramGPT: Carry a GPT in your pocket

Okay, I guess GPT was already in your pocket - but not as easy as this! After getting tired of constantly reminding openAI that I am indeed a human, I decided to take matters into my own hands. Hosting a personal Telegram bot on a Raspberry Pi which calls the API of the world’s new favorite AI friend seemed like a worthwhile project. Also, it is a good intersection of various buzzwords, and is therefore also a worthwhile blog post.

DALL·E 2’s interpretation of: “A futuristic intelligent humanoid robot using an antique telegram machine”.

DALL·E 2’s interpretation of: “A futuristic intelligent humanoid robot using an antique telegram machine”.

Coding on a Raspberry Pi

This little coding story starts with it being the week of my birthday, and a friend of mine asking me what it is I wanted as a gift. He had traveled to visit me in Cambridge (UK), and when he asked me that, I knew that we were just minutes walk from the only physical Raspberry Pi shop in the world (or so I am told). I had helped this friend build his first gaming PC a year or so earlier, so there was something poetic about it. I traveled home excited by my new pocket-sized computer.

But what is a Raspberry Pi good for? What project would I choose that couldn’t just be done within my usual setup? I had recently heard of how easy it was to create Telegram bots, which would allow you to automate certain tasks and communicate easily with it from either a phone or a browser. This, combined with my frustration at constantly logging in to use chatGPT, and constantly ticking a box to prove my human status, led to the idea. There is nothing revolutionary in this project at all. In fact, it is quite basic for many developers. For me, however, it exposed me to new ideas like the infinite polling loops while waiting for messages, communicating via API keys, user authorization with ID, persistent state in databases, etc.

While this blog doesn’t aim to be a tutorial, I hope some other aspiring developers or code enthusiasts will enjoy a slight demystifying of concepts here, and perhaps a bit of inspiration for their own projects.

DALL·E 2’s interpretation of: “A futuristic intelligent humanoid robot using an antique telegram machine”.

DALL·E 2’s interpretation of: “A futuristic intelligent humanoid robot using an antique telegram machine”.

Setting up the Telegram bot

Telegram bots are super easy to set up. If you are using Python like me, then this page shows you most of what you need. The starting code they provide looks like this:

import telebot

bot = telebot.TeleBot("YOUR_BOT_TOKEN")

@bot.message_handler(commands=['start', 'help'])

def send_welcome(message):

bot.reply_to(message, "Howdy, how are you doing?")

@bot.message_handler(func=lambda message: True)

def echo_all(message):

bot.reply_to(message, message.text)

bot.infinity_polling()The code imports the telebot module and creates an instance of the TeleBot class, which takes the bot token as an argument (this is a unique key for your bot, don’t share it with anyone!). The TeleBot instance provides a function decorator which allows you to register handlers - functions that are called in response to messages the bot receives or over events.

The first handler responds to the commands /start and /help. The second responds to all other messages, in this case, by just repeating the message back. Two interesting points here: first, the handlers are essentially checked top to bottom, so sending the message /help is answered by the first and only the first handler. Second, the lambda function is true for any and all messages, making this a great way to capture every message that didn’t pass a previous check.

Oscar Wilde said, “Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery that mediocrity can pay to greatness.” Let’s make our mediocre bot less flattering and actually make it say something new and interesting rather than imitating the user. We will do this by forwarding messages to the openAI API, essentially getting a chatGPT response.

Setting up the OpenAI API

First and foremost, it is worth noting that the openAI API is not free, unlike chatGPT. You will have to create a paid account and get an API key which charges you (again, don’t share that key!). However, it is extremely cheap! The chatGPT model we will use in this project is gpt-3.5-turbo, which costs $0.002 / 1K tokens. Tokens aren’t very easy to count, but think along the lines of 2 or 3 tokens per word. To get started with calling the API, check out this example. In particular, they show an example like this:

import openai

openai.ChatCompletion.create(

model="gpt-3.5-turbo",

messages=[

{"role": "system", "content": "You are a helpful assistant."},

{"role": "user", "content": "Who won the World Series in 2020?"},

{"role": "assistant", "content": "The Los Angeles Dodgers won the World Series in 2020."},

{"role": "user", "content": "Where was it played?"}

]

)The interesting thing to note here is that whenever you ask your friendly bot something new, you have to show it all the previous conversation with each message listed as “user” or “assistant” respectively. The system message simply gives some context for the language model. Calling the ChatCompletion.create function will return a dictionary with the response and some other information. The response can then be sent back to the user of the Telegram bot, and the conversation thread grows.

Seeing how the API works led to a big design choice in this project, which is to have a ConversationThread class that can store each response, have its tokens counted, and can be instantiated for each user of the Telegram bot. Importantly, the conversation can be cleared. This must be an option since no more than 4096 tokens can be sent to the API (this is model dependent; gpt-4 will greatly improve on this).

So that is basically it in terms of background. Everything else comes down to how you choose to weave these two tools together. Below I will discuss some of my own design choices. I have no doubt that everything I did could have been done in infinitely better ways.

Combining the two

I wanted to make absolutely sure that nobody could message this bot without my permission, but I didn’t want it to be limited to just me. I created a series of authorization checks that extract the user id from a Telegram Message object. These checks should be applied to every handler function the bot has. I chose to define a decorator factory which could then be applied to every function. This solution is repetitive but is fine for the small number of functions our bot will contain. If I had to refactor this, I would probably create an inheritance hierarchy of callable classes and use something akin to the decorator design pattern described in the famous Gang of Four book (alternatively, see it here). Here is my code:

def whitelist_filter_factory(bot, whitelist):

def whitelist_filter(func):

def wrapped(message):

if message.from_user.id in whitelist:

func(message)

else:

response = "Your id is not whitelisted to use this bot."

bot.send_message(get_chat_id(message), response)

return wrapped

return whitelist_filterThe reason this is a decorator factory rather than just a decorator is because I need the bot to be taken as an argument so we can warn the user if they’re not whitelisted. I created a similar decorator for adding new users if they are whitelisted but not yet in the database of conversations. Both these decorators will be seen in the final code snippet at the end of this blog. The code snippet above explicitly assumes the function being decorated only takes “message” as an argument. This is an unnecessary limitation but fine in this context since handler functions only receive one message.

A second design choice is that I wanted conversations to be preserved, even if the bot goes offline (e.g., the Raspberry Pi turns off). The idea of having persistent state is ubiquitous in so much of programming, and consequently, there are arbitrarily many databases to choose from. In my personal coding experience, this is a new venture for me, as normally I run a script with inputs and simply save the outputs for analysis later. I don’t often use long-term “recall” of some memory multiple times in the program. I, therefore, didn’t want to use a black box as my database, instead choosing a low-tech solution I could see more clearly. I chose to save a dictionary with keys being user ids (extracted from the Telegram Message object) and values being a UserProfile class. That class, in turn, contains the name of the user and a current ConversationThread. This database was saved and loaded as needed using Pickle. The idea of Pickling is to save an arbitrary Python object as serialized data. In the end, my crude database usage looked something like this:

from pathlib import Path

import pickle

def load_db():

with open(PICKLE_FNAME, 'rb') as file:

obj = pickle.load(file)

return obj

def save_db(db):

with open(PICKLE_FNAME, 'wb') as file:

pickle.dump(db, file)

def get_user_profile(user_id):

db = load_db()

assert user_id in db, "User id not currently in the database"

return db[user_id]As mentioned earlier, I also added a decorator factory for adding new users. This will add users to the database and ensure the assert statement is never triggered.

More advanced commands

Earlier we saw how to define commands. Let’s now write some commands which will help us control the bot. I also mentioned previously that tokens build up throughout a conversation and must be routinely cleared (just like starting a new conversation on the usual chatGPT). I defined two commands /count and /clear which did these tasks. For counting tokens, a useful code snippet is given here. Clearing the conversation was as simple as loading the corresponding UserProfile from the database and clearing the currently stored messages.

Some other commands I defined were an /init, which takes a new user’s name. Also, a /help command, which simply tells the user what the bot is and what other commands exist. One final command I defined is probably terrible practice, but it was interesting and helpful in debugging. It turns out that you can easily terminate and rerun a Python code from within the Python code itself, so my workflow became a back and forth between typing new Python code and then messaging the bot itself on Telegram with a /restart command!

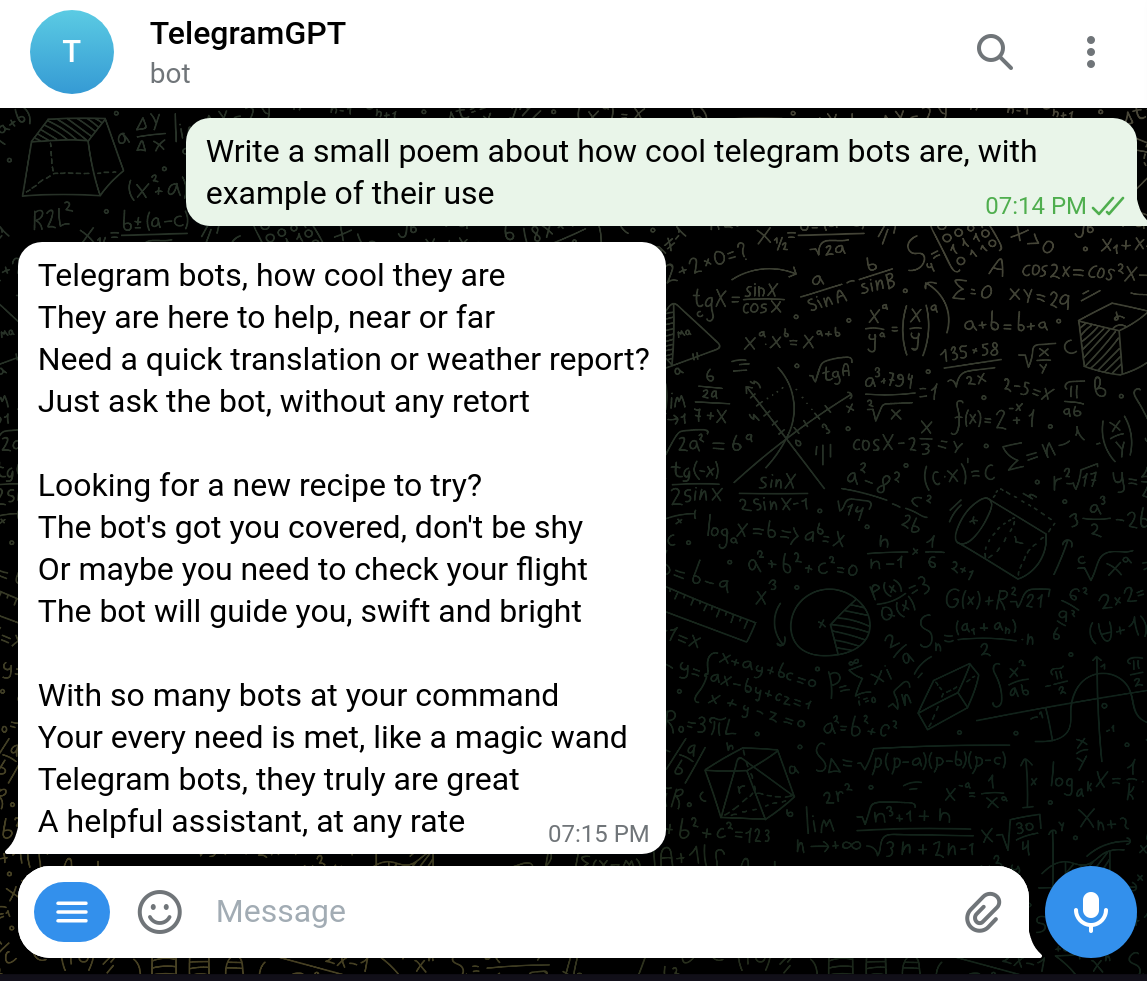

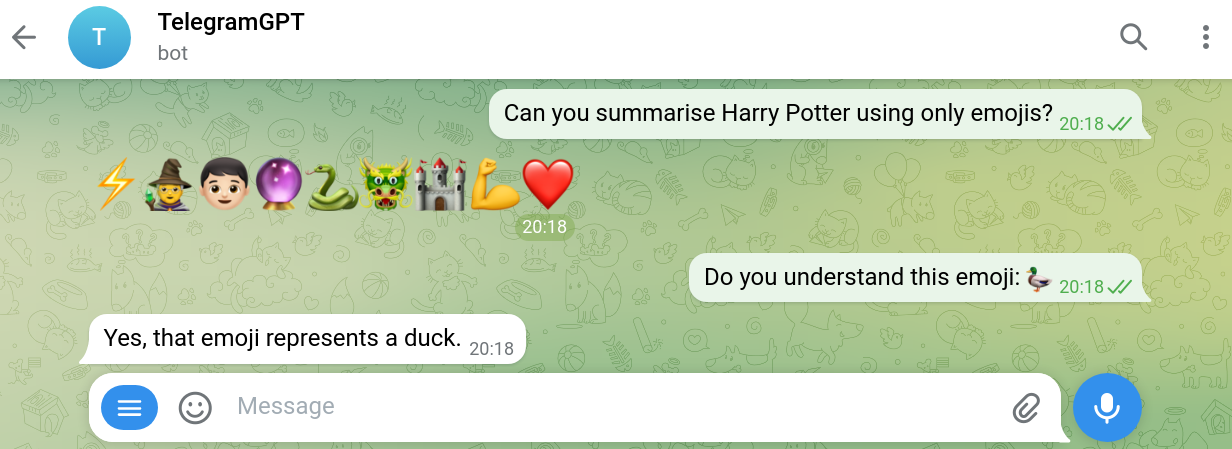

In general, debugging became a surreal experience since I could, in some sense, talk to my code. For example, my way of checking if emojis were a dangerous edge case was to ask the bot “do you understand this?” and send a duck emoji. It proceeded to describe to me what a duck is. No need to check for emojis!

GPT has no problem understanding emojis (or the story of Harry Potter apparently).

GPT has no problem understanding emojis (or the story of Harry Potter apparently).

The bottom line

As a bottom-line result to this blog, I will show the main function that sends GPT responses to the user:

# MESSAGE HANDLER

@bot.message_handler(func=lambda msg: True)

@whitelist_filter_factory(bot, WHITELIST)

@new_user_factory(bot)

def chatGPT_call(message):

user_id = message.from_user.id

text = message.text

date = message.date

user_profile = get_user_profile(user_id)

user_profile.current_conversation.add_message(Message(text, "user", date))

response_json = conversation_api_call(user_profile.current_conversation.open_ai_format())

response = response_json["choices"][0]["message"]["content"]

user_profile.current_conversation.add_message(Message(response, "assistant", date))

save_user_profile(user_id, user_profile)

bot.send_message(get_chat_id(message), response)A lot of this code delegates responsibility to other smaller functions (as code should!), but hopefully it illustrates the different building blocks of this project. This function responds to all messages that didn’t trigger a previous handler function (one of those is a regex check for an unknown command). The code then assumes it is a GPT prompt. First, it retrieves the user id from the message and loads the corresponding UserProfile from the database. Then it adds the new prompt as a message from “user”. This is forwarded to the openAI API, and the response content is extracted from the dictionary. This is also added to the conversation as being from the “assistant”. The new conversation is saved back into the database for safekeeping, and the bot gives the response to the user.

Future ideas

This project has honestly been very useful, and it is now my favorite way to interact with chatGPT. It is easy to quickly send a message when you are on the go, and in one case I even sent a message while I had no internet access, knowing I would get a response as soon as I was back online.

To take the project further, I plan on adding new features. Firstly, I would like to add a logging system since I’d like to keep track of what goes wrong and how to fix it (from the user end you will just never get a response, without knowing why). Also, I would like to know if some user who isn’t whitelisted tries to use the bot. Secondly, I want to be able to /save and /load conversations akin to what chatGPT has. This way, some interesting ConversationThread could be saved for later. I would also add a /remind command to see what that whole conversation was, without using any more tokens. A final learning opportunity I plan to derive from all this is to create a Docker container for this project, making it easier to host on the Raspberry Pi without simply leaving a terminal in an infinite polling state. This might also allow me to automatically redeploy the bot from the main branch of a git repo. This way I could stop the tedious process of accessing the Raspberry Pi through SSH.

I hope this blog served as inspiration for someone to try this for themselves! If you do, then please reach out to me on LinkedIn or by email and let me know how it goes.